En avrill’auteur de livres pour enfants à succès Shannon Hale a publié le livre numéro 10 dans son livre acclamé Princesse en noir série. Pour ceux qui n’ont pas d’élève du primaire dans leur vie et qui ne sont donc peut-être pas aussi familiers avec la série que moi, voici l’essentiel : Prim Princess Magnolia vit dans un charmant château faisant des choses délicates de princesse avec sa licorne Frimplepants jusqu’au ” alarme monstre » sonne. Ensuite, Magnolia se transforme en une guerrière coriace et combat des monstres maladroits mangeurs de chèvres tout en criant des commandes comme “Comportez-vous, bête!” Dans son dernier ajout, Princesse en noir et prince en roseHale nous présente l’un des nouveaux amis de Magnolia, un prince qui aime porter des capes, des tuniques et des collants [the shade of tropical flamingos.

Like the previous books in the series, Prince in Pink was a commercial success and quickly racked up hundreds of positive reviews online. “What a sweet, wonderful addition to the series,” gushed one five-star review. “I love that the canon of superheroes keeps growing, and that they’re all so different from one another.”

But not everyone was so effusive. Twenty-five percent of the book’s Amazon reviewers were so offended by the mere presence of the prince, they gave it the damning one star. “Why does this series need an effeminate boy character?” wrote one unhappy reviewer, summing up the complaints. “This is just another grab to warp a fun series for children into a tool for woke indoctrination.”

In a Twitter thread a few weeks after the book came out, Hale addressed the hypocrisy of readers who embrace a strong female character but reject a male character who isn’t conventionally macho. “A girl who wears black and fights monsters: acceptable,” she wrote. “A boy who wears pink and likes to decorate for a party: wrong.” Dozens of readers replied, many of them expressing gratitude for Hale and her characters. One enthused, “My little tough-as-nails girl and my boy who likes to cuddle and sing, LOVE your stories. Buying this one now—can’t wait to introduce them to this sweet prince in pink!”

Most authors would have ignored the rest of the comments and moved on. But Shannon Hale is not like most authors. A few days later, she returned to her thread and added a tweet. “I feel so much compassion for this reviewer,” she wrote. “Like me, she grew up in this world that demeaned the feminine. That told her that who she is, is fundamentally shameful.”

Much like her princess protagonist, Hale—who has written dozens of other books for kids and teens—moves between two worlds. As an author, she gives passionate talks about the value of including people of all races and genders in children’s literature. On Twitter and in her newsletter, she speaks out against policies that she considers hateful—abortion bans, for instance, and rules that seek to limit gender-affirming medical care. In recent months, she has vociferously opposed the rising tide of book bans, especially in her home state of Utah.

Hale’s other identity is as a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. During times of such polarization, her life as both a liberal activist and a Mormon can appear confounding. In her 2017 book Real Friends, the first in her trilogy of graphic novel memoirs about her childhood and early adolescence, she included imagined conversations with Jesus that she had as a child. One apparently secular reviewer on GoodReads complained, “I honestly think this was just about Jesus. There was no warning for all the religious propaganda and imagery.” Other, presumably more conservative, readers objected to what they saw as inappropriate themes in the book, such as kids kissing. “Progressive people are kind of suspicious of me,” Hale tells me, laying out the dynamic. “And then for books that I’ve written that never even had a single cheek kiss, I’ve gotten hate mail from conservative people.”

Though it seems to irk plenty of parents, this moving between two communities is part of what makes Hale good at creating characters that children love. For “students who have not always had access to books where they can see themselves, their family, their peers,” said Kasey Meehan, who leads the initiative against book bans at the reading advocacy group PEN America, “her message is the opposite: You do exist, your story does matter.”

In a report last year, PEN America found that more than 1,600 books had been banned in the 2021-2022 school year alone, most of them because of identity themes—gender, race, and sexuality. While not explicitly dealing with those themes, at their core, all Hale’s work concerns a nearly universal subject intimately related to identity: how it feels to be a child who doesn’t fit in.

But not everyone wants to admit that children often feel different and left out. Behind every book ban, Hale told me, are parents and school administrators scared of the rapidly changing world—a contemporary echo of her own conservative Mormon upbringing. In the grand tradition of Judy Blume or Beverly Cleary, Hale is very much a spokeswoman for her times. She seems to appreciate the fact that she can act as a kind of bridge between worlds—or maybe as an ambassador. As any reader of Princess in Black knows, the so-called monsters aren’t always what they seem.

On a chilly morning in April, I drove 40 minutes south from Salt Lake City to Saratoga Springs, Utah, to watch Hale give an assembly at Thunder Ridge Elementary School. The sun illuminated the snow-capped Wasatch mountains, and I could see why the Mormon pioneers chose Utah as their Zion. As I approached Saratoga Springs, both sides of the highway were flanked by developments carved into the gently rolling foothills. The houses were unfancy yet enormous—giant earth-toned boxes with play structures in the back, designed to accommodate large families. One of them had a tube slide snaking down from the front porch into the backyard.

At Thunder Ridge, about 200 kindergartners through third graders filed into the cavernous gymnasium, their teachers gamely directing traffic. Hale’s twin nephews, third graders at the school, shyly shuffled up to the front to introduce her, informing their classmates that they knew the famous Shannon Hale not only because of her books but also because she was their aunt.

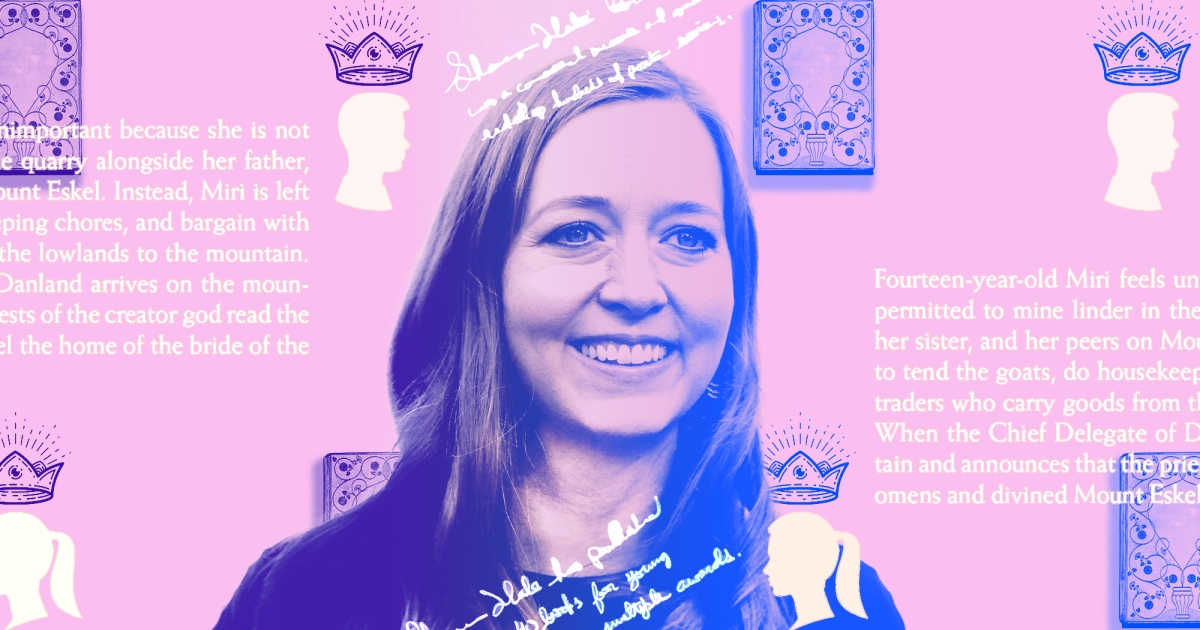

Tall and willowy with chin-length reddish brown hair and chunky glasses, Hale was dressed in loose jeans and a drapey cardigan. Moving comfortably among the sea of kids sitting crisscross-applesauce on the gym floor, she recounted that the first story she ever wrote, in kindergarten, was about a witch who ate babies, noting that its creation coincided with the birth of a new sibling—possibly not a coincidence. The kids giggled with delight—there was something just a little bit naughty about that reference—and supremely relatable.

Thunder Ridge Elementary is part of Utah’s Alpine School District, which made the news last year when parents called for a review of 52 titles and schools removed 22 books from libraries. Hale’s books weren’t on the list, but those with LGBTQ themes were, including Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe and All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson. Most of the propulsion for the purge came from a local conservative group called Utah Parents United, which directed parents to a Facebook group called LaVerna in the Library, a local offshoot of a national network of groups that encourage parents to snap photos of books that they consider unfit for children and send them to local legislators.

On the day that I glanced through the LaVerna page, someone had just shared an article titled “Chelsea Clinton Comes Out in Favor of Porn for School Kids.” A group member commented, “Unsurprising. What was surprising was Shannon Hale & all the Utah authors she got to sign her letter. Which is why I’ll never recommend or read her books again.” The commenter was referring to a petition that Hale had circulated last year, which stated, in part: “We ask our Utah school districts, library boards, state and local governments, and all those in power to reject these divisive, hate-mongering attempts to limit whose stories are worth telling.”

A few days before Hale’s school assembly, I spoke to Trudy Bezant, Thunder Ridge’s school librarian. Bezant said that local elementary schools like hers had been largely unaffected by the book bans, although the previous year, when the district had its wave of bans, a parent had complained about a popular book called Drama by Raina Telgemeier. She did so, she said because it was “along the lines of same-gender attraction.” The parent didn’t end up officially pursuing the complaint, and the book remains in the library. Bezant said she thought the parent might have been concerned because of the book’s graphic novel format, which makes it accessible to younger children who “are coming upon more mature topics,” she said. “For the chapter-book format, they would not most likely be reading it, you know, in first grade.” As for Shannon Hale, she said the school had invited her because of her books’ incredible popularity with students of all ages.

Hale grew up in a large Mormon family in Salt Lake City, where she still lives with her husband and four teenagers. She stopped going to church shortly after Donald Trump was elected president—she was crushed that so many Mormons voted for him. Though she still sees good in the church and considers herself a Mormon, she came to realize that she could no longer be in community with people who had tacitly endorsed Trump’s misogyny and who upheld the church’s rejection of LGBTQ people. Still, there was a genuine sense of loss. “I am Mormon,” she told me over giant plates of mole at the Red Iguana, a Salt Lake City institution that she has been frequenting since she was a teenager. “I was born and raised in it. And generations back—it isn’t like something I can just pluck out of myself. It’s still who I am. But I don’t quite belong there. And I don’t belong anywhere.”

In fact, she always felt different from the others in the tightly-knit Mormon neighborhood where she grew up. Even as a young child in the 1980s, she loved reading and writing. But within a religion where girls’ ambitions were restricted to creating a home and having lots of children, she dreamed of being an author. As a teenager, she began to see that being different could not only be okay—it might even be good. Right before she started high school, Salt Lake City rezoned its districts, and Hale ended up at a school across town that was much more socioeconomically and racially diverse than the one she was previously zoned for. “I loved it,” she told me. “I was this white girl in a conservative community, but finding these pockets of space that were very diverse—it opened up my mind to the idea that there’s more than one way to be.”

Around that same time, Hale immersed herself in the world of fantasy books—Lord of the Rings, Narnia, and Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain Chronicles—and noticed that boys were the protagonists in all her favorites. It wasn’t until later when she had decided to pursue a master’s degree in creative writing at the University of Montana, that she set out to write a fantasy book with a female main character. She had originally envisioned it as a retelling of a Brothers Grimm fairy tale, for adults, but then an agent told her she thought it could fit into a newish genre for teenagers called young adult. “It made sense,” she said. “My internal reader was a combination of when I was 10 to 14, saying [about reading] ‘Oh, c’est la joie! C’est l’amour!’ Et c’était aussi moi maintenant avec ma maîtrise et mes sensibilités littéraires. Le livre, Fille d’oiea été publié par Bloomsbury en 2003 et est devenu un succès critique et commercial.

Écrire pour les enfants a permis à Hale de canaliser le genre de joie qu’elle avait ressentie en tant que jeune lectrice et au cours des années suivantes, sa carrière a décollé. En 2005, Académie des princesses a remporté un Newbery Honor , la plus haute distinction en littérature pour enfants, avec des lauréats précédents dont EB White’s La toile de Charlotte et Beverly Cleary’s Ramona Quimby, 8 ans. Plusieurs autres livres bien reçus sont apparus, y compris un récit du conte de fées Rapunzel appelé La vengeance de Raiponce en 2008 et sa suite, Calamité Jack, deux ans plus tard.

La première Princesse en noir livre est sorti en 2014 et les ventes ont décollé. À ce stade, Hale gagnait suffisamment en tant qu’écrivain pour que son mari Dean quitte le travail de bureau qu’il n’a jamais vraiment apprécié et commence à collaborer avec elle. Il a également pris le relais à la maison – à ce stade, leur famille s’agrandissait – lorsqu’elle était sur la route. Hale a décrit Dean comme le “gars des idées”. Par exemple, disons qu’elle a besoin d’un nom amusant pour un restaurant, “il m’enverra un e-mail avec 25 suggestions”, dit-elle. « C’est ce genre de gars. Il est génial comme ça.

Sa renommée croissante, cependant, a conduit à une lutte personnelle plus profonde sur son identité. En découvrant sa religion, les gens qu’elle a rencontrés en dehors de l’Utah ont pensé à Donny et Marie Osmond, ou au livre de Jon Krakauer sur les mormons fondamentalistes. Sous la bannière du ciel. « Je ne veux pas tout représenter, car cela ne me représente pas », m’a-t-elle dit. « Je suis un membre dissident de cette église, je ne suis pas d’accord avec tant de choses. C’est aussi la communauté aimante dans laquelle j’ai grandi et dont ma famille est originaire. J’ai tellement d’amour et de compassion pour eux, je ne vais pas les rejeter.

Alors que nous nous asseyions et discutions, deux mères partageant de la nourriture mexicaine, à plusieurs reprises, la conversation est revenue à l’identification intense de Shannon avec les enfants et leurs parents. Elle se sent pour les enfants qui ne s’intègrent pas – pour les enfants homosexuels et les enfants de couleur et les enfants aux prises avec des problèmes de santé mentale – et aussi pour les parents confus et même effrayés qui peuvent trouver leurs enfants méconnaissables. Une fois, elle et deux de ses filles sont apparues au Capitole de l’État de l’Utah, lors d’un événement anti-interdiction des livres où elle a pris la parole. Alors qu’ils partaient, un homme lui a crié: «Mes enfants sont de grands fans de Princesse en noir. Je suis tellement déçu de toi. Elle se souvient : « Je suis devenue thérapeute ! J’étais comme, ‘C’est bon. C’est normal d’être déçu. Je ressens de la compassion pour lui. Il est là où il est dans sa vie, et il fait de son mieux là où il est.

Puis nous avons commencé à parler de livres pour enfants. Mes deux enfants sont plus jeunes que ceux de Hale, et j’ai avoué que je détestais vraiment Capitaine Slip, une série de Dav Pilkey tellement scatologiquement resplendissante que j’ai dû l’interdire avant l’heure du coucher pour mon fils de sept ans. Il était tellement titillé par toutes les blagues sur le caca et le pet qu’au moment où nous terminions un chapitre, il ricochait pratiquement sur les montants du lit.

“Qu’est-ce que tu n’aimes pas exactement Capitaine Slip?” demanda-t-elle, à part les retards à l’heure du coucher bien sûr. J’ai réfléchi une minute, puis j’ai répondu que je craignais que mon enfant n’apporte l’humour du petit pot à l’école, et cela aurait une mauvaise image de moi en tant que parent. Hale hocha la tête. “Ce livre est subversif pour eux – ils savent que c’est méchant”, a-t-elle déclaré. « Ils savent qu’ils ne peuvent pas parler comme ça devant leur professeur à l’école. Mais quel sûr façon d’être méchant. Elle m’a gentiment informé qu’il n’y avait pas d’univers possible dans lequel ma délicate fleur ne faisait déjà des blagues de pets avec ses copains. Avec Capitaine Slip, dit-elle, Pilkey a «donné notre voix aux garçons qui ont été envoyés pour s’asseoir dans la salle, et il a dit que vous comptez toujours. Et c’est normal que tu trouves ça drôle, et tu es toujours vraiment embrassé. Oui, elle avait raison. Je me sentais mieux, en fait.

Et puis j’ai réalisé : j’avais juste été Shannon Haled.

De retour au tonnerre Ridge, lorsque les enfants plus âgés (quatrième, cinquième et sixième année) sont arrivés, elle a demandé aux garçons s’ils aimeraient lire Académie des princesses. « Noooon ! » gémissaient-ils à l’unisson. “Beaucoup de gens pensent que les garçons ne peuvent pas lire un livre avec ‘princesse’ dans le titre”, a déclaré Hale en souriant. “Ils ont tort !” Avant que les garçons ne puissent protester, elle a montré des photos d’hommes lisant Académie des princesses dans toutes sortes de situations viriles. “Les garçons lisent Académie des princesses Au parc! Ils l’ont lu avec une moustache, avec des outils électriques, en faisant de l’escalade dans la Batcave ! Les enfants ont craqué.

Elle leur a ensuite montré des illustrations de sa série de romans graphiques de mémoire. Un thème majeur est l’amitié – les alliances changeantes des préadolescentes. Elle a décrit ses propres années d’école quand une fille de la clique populaire était gentille avec elle certains jours mais méchante avec elle le lendemain, apparemment sans aucune raison. Sur le rétroprojecteur, elle a montré une illustration représentant Shannon, une quatrième année, jetée sur un navire à travers une mer agitée. Elle a demandé aux enfants de lever la main et de lui dire comment ils pensaient qu’elle devait se sentir.

“Tu es seul!” a appelé un enfant.

“Je suis seul! C’est un grand détail. Quoi d’autre?”

“Il y a une tempête !” cria un autre.

“Bien, donc ça semble dangereux”, a déclaré Hale. “Encore une chose que je veux que vous remarquiez, c’est qu’il n’y a pas de commandes sur le bateau. Il n’y a aucun moyen de le diriger. Il y a donc la petite Shannon et elle n’a aucun contrôle. Vous regardez cette image, vous ressentez et vous comprenez comment elle est sentiment.”

Le problème avec les guerres culturelles, c’est qu’il n’y a jamais de gagnants. Pourtant, au cours de ces dernières années très chargées, un groupe de perdants est clair : les enfants. Pris au milieu de débats houleux (et parfois violents) sur les masques, les vaccins et le programme scolaire, que doivent-ils penser des adultes qui leur disent de se comporter mais n’arrivent pas à faire de même eux-mêmes ? La seule véritable constante dans ce paysage controversé sont tous les jeunes lecteurs, dont la vie peut littéralement être transformée parce qu’ils lisent quelque chose d’étonnant dans un livre.

Après l’assemblée, je me suis dirigé vers Hale, qui était entouré d’une foule d’enfants et d’enseignants. À la périphérie du groupe, j’ai rencontré une fille de dix ans, l’un des seuls enfants noirs que j’ai vus à Thunder Ridge ce jour-là. Elle serrait son exemplaire de Meilleurs amis, le deuxième livre de la série de mémoires de Hale, alors je lui ai demandé ce qu’elle aimait à ce sujet. “Elle explique ce qu’elle ressentait quand elle était enfant en sixième”, a déclaré la fille en souriant. Je lui ai demandé si elle pouvait comprendre les sentiments que Hale décrivait. Elle acquiesça. “Je suis très timide,” dit-elle doucement. “Cela m’a fait me sentir chez moi.”

La source: www.motherjones.com